Stepping Outside the Story: Writing About ‘Difficult Things’ in Non-Fiction and Life Writing

by Madri Kalugala

There is a Buddha Doodles quote (if you haven’t heard of Buddha Doodles, do check out the lovely cartoon art series by Molly Hahn!) that I came across some years back and that has always stayed with me, which says, simply: “Step outside the story”. While the line itself is simple, as well as the adorable cartoon illustration accompanying it, the idea behind it is quite deep, with its execution often being extremely difficult.

Mirroring the Buddhist ideals of detaching yourself from the events that happen to you in life, to “step outside the story” essentially means to break away from your narrative – your perception of a given event, the stories you tell yourself about the way things happened. It requires us to stop identifying with the events of our life, and become objective observers to the course of events that unfold – an act that requires great tenacity. In modern day psychology, this has also become a method that is increasingly used in therapy, such as in CBT and cognitive defusion techniques, which “derive from mindfulness practices designed to detach from the content of the mind”. Also known as deliteralization, the practice essentially comes down to loosening the grip of thinking on our identity – fostering objective, mindful observation of life events, and creating distance from our thoughts and the ‘stories’ we tell ourselves.

Needless to say, this process is not an easy one. Especially if we have undergone trauma, have witnessed distressing life events or have complex post-traumatic stress (C-PTSD). It is incredibly hard to view traumatic events from an objective distance – to revisit traumatic moments in life as a passive witness. However, if we are ever to write non-fiction, it is an essential practice that we have to train ourselves in as writers: the practice of distancing ourselves from the story when writing about difficult things.

Like so many of us, I turned to writing from a young age as a means to cope; an outlet for the emotions that were too big to contain and that swelled up inside me like giant pus-sacs, near to bursting. Often also, I used writing as a means of working through a problem or issue that felt too complex, too heavy to work out alone in my head. Hence, the process of writing often felt like free therapy – especially in the poetry form, which was the medium I worked in for the longest time. So when my own writing naturally began to take a turn towards non-fiction, many years and multiple traumas later, I found myself with a wealth of material and a lot that I wanted to say. Hemingway says, “Write the truest sentence that you know.” He also says to sit at a typewriter and bleed. But in order to be able to do this, I had to first stop living in my story – to stop feeling it, reliving it, being immersed in it. Because to write from inside the story was too traumatic, too draining, too harrowingly painful. So, I had to make myself do what that little Buddha Doodle said: I had to step outside of the story.

The once-prominent Harvard psychologist Dr. Richard Alpert (later turned spiritual guru, Ram Dass) echoed this as a deep truth, stating: “Everything changes once we identify with being the witness to the story, instead of the actor in it.” Learning to write non-fiction is a lot about this — about bearing witness. And one is required to do this – bear witness – with compassion: often not only for the others in our story, but for ourselves. This, ultimately, would be the crucial factor in saving one’s non-fiction writing from falling into the potential trap of mere navel-gazing.

I had to learn this the hard way, of course. Trying to write out a memoir, or a personal essay, or a non-fiction piece, I would always find it difficult to proceed after a certain point. I would find myself getting stuck in the narrative. Because, contrary to what Hemingway said, bleeding out your truth is not easy. The trauma, the memories, your mind’s stored version of events, takes over. Objective distancing and passive observation are all excellent in theory, gruelling in practice. Often, I catch myself becoming caught up in the emotions triggered by memories of events while I try to write them out. Attempting to write non-fiction, you are also filled with self-doubt: what is ‘truth’, anyway? If human memories are unreliable, and there are multiple truths and realities— why even try to write one’s narrative of events? And the looming, more existential question: who would my version of truth or my ‘story’ matter to, anyway?

But then, who do we write for, really – ultimately? A lot of us writerly types like to claim that we write for ourselves, first and foremost. That all we want to do, really, is tell ‘our story’. What the process of attempting to write non-fiction taught me, however, was that a person’s life story was just that: a story. So, I learnt that I had to train myself to stop viewing life from the many-coloured lenses of my emotions: to stop identifying that ‘I’ was the main character to which all these things happened. Of course, I still do struggle with this – with detaching myself to that extent – but the truth is: it has made the process of life writing that much easier. Learning to step out of the story is, then, the first step of becoming able to write it more fully, more authentically, more ‘truth’fully.

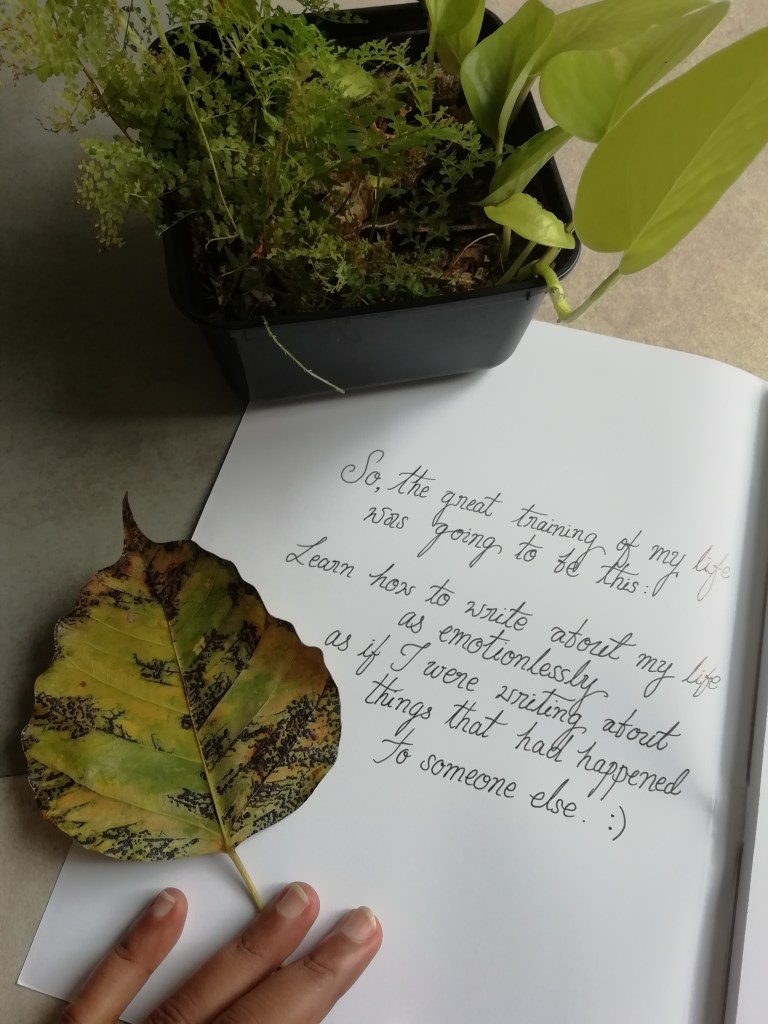

In 2021, I once wrote in a journal entry: “The greatest training of my life would be learning to write my story as if it had happened to someone else.” Three years later, I am still trying – trying to practice the detachment and emotional mastery needed to accomplish this. But I know, once I get there, the stories will flow more freely – and, in turn, free me.

Madri Kalugala